5 radical reasons to rethink your global TV strategy

Covid-bump aside, it’s old news that traditional TV is in decline the world over. Once the CEO of our comms, it’s now a valued member of the board, jostling with the rising stars of streaming and online video. As new data reveals a complex and fast-fracturing picture across markets, we’ve got five challenges to help you reset.

To analyse global shifts in consumption, we used GWI data. GWI is the world’s largest survey into consumer media behaviour, covering over 40 countries and over 18 million consumers. We analysed 33 waves of data from Q4 2012 up to Q1 2021, providing a single global view of the fast-changing dynamics of the global TV landscape.

Provocation 01: Let each market, not a region, be your guide

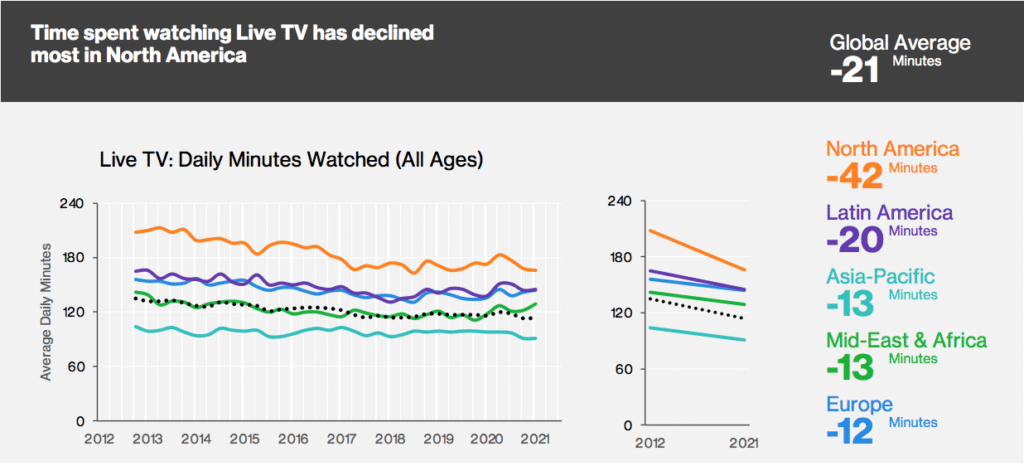

Just-in viewing numbers for Q1 of this year reveal the continued reduction in linear TV across the globe. North America shows an outsized drop-off, with the rest of the world on a broadly similar slow-but steady downward path.

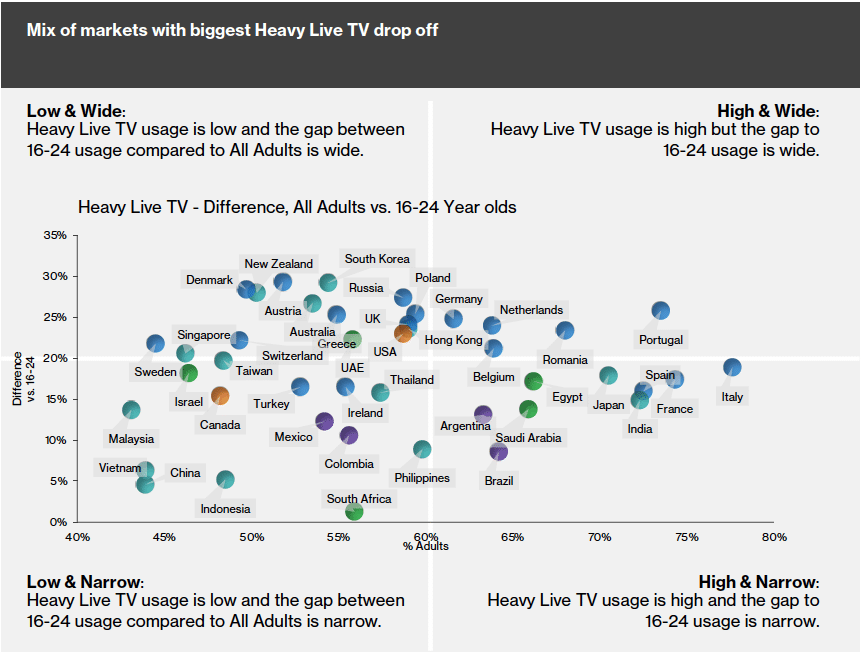

When you focus on this data, a whole new world opens up – one with less regional consistency. In some European markets, like Portugal for example, TV viewing has held up pretty well, but the gap between the older and the younger has become a chasm. In other markets like Brazil, TV viewing has held up better for all audiences. Australia and New Zealand have copped both sides of the double-edged sword – TV viewing has dropped overall, and the youngest cohorts have dropped even faster. In China, South Africa and Indonesia, TV viewing hours have held up better for most viewing demographics (or at least appear to have reached a plateau).

What’s interesting lies beneath the curves, in the distribution of those declines. As pioneering sci-fi writer William Gibson said, ‘The future is here, it just isn’t evenly distributed’. The key is to look not just at the pathway of a TV market but at that market’s shape. In particular, how much faster are younger audiences (especially the 16-24s) declining than middle aged or 55+ ones? Put another way, to what extent is TV becoming a ‘medium for old people’ in that market?

When you focus on this data, a whole new world opens up – one with less regional consistency. In some European markets, like Portugal for example, TV viewing has held up pretty well, but the gap between the older and the younger has become a chasm. In other markets like Brazil, TV viewing has held up better for all audiences.

Australia and New Zealand have copped both sides of the double-edged sword – TV viewing has dropped overall, and the youngest cohorts have dropped even faster. In China, South Africa and Indonesia, TV viewing hours have held up better for most viewing demographics (or at least appear to have reached a plateau).

The first task for any planner in trying to solve a problem like linear TV’s ongoing (or otherwise) role in the media mix, is to really understand the challenge from as many angles as possible. What is the true nature of the problem? Are we keeping some audiences better than others? Are we losing everyone or are we simply failing to gain and hold the youngest? These are questions that can no longer be answered at a regional level.

Provocation 02: Replacement vs Reinforcement – plugging the gaps for younger viewers

There’s no doubt that the biggest impact of TV’s decline has been among the youngest audiences. But it’s also easy to overplay this hand. The young have consistently watched less TV since the dawn of commercial television. Even in a turbulent TV market like Australia, a schedule with 700 GRPs in it would still reach 40% of under 39s, at least three times.

Find me another channel that can do that: audio-visual, full screen, sound on, with high attention levels! There isn’t one! That said, the numbers tell a crystal-clear story:

The average North American 16–24-year-old watches 56 fewer linear TV minutes a week than nine years ago. This is a drop of one third in daily live TV viewing time from 2.9 hours in 2012.

The average European 16–24-year-old watches 46 fewer linear TV minutes a day than nine years ago. A fall of 35% from the 2.2 hours reported in 2012.

The average Latin American 16–24-year-old watches 33 fewer linear TV minutes a day than nine years ago, a 22% decrease from 2012.

Even this isn’t uniform. In some markets where access to TV is still growing, the decline is much less marked. In MENA, for example, the difference is a rounding error in the data and in APAC there are huge varieties of experience market by market (with some still showing Linear TV in growth).

All of this means that marketers need to think a bit harder – and by market development stage – about where and how to talk to the youngest audiences. When selecting a blend of channels to engage audiences, we’re looking for a mix of four key factors:

Reach (and rapid reach at that)

ROI/cost effectiveness

Influence of channel in the customer journey

Impact/attention

For many audiences, TV still ticks all four. If it doesn’tin your market or for your audiences – especially those fast-disappearing young consumers – then which channels do you need to fill in with? Which tasks need to be done elsewhere? Has TV lost its ROI? (In which case you’ll need some hard-working acquisition or cheaper channels.) Has TV lost its impact? (In which case you might want to find some channels that dial up emotion.) Find what TV is weakest at for your local youth audience and reinforce that area with remaining budget.

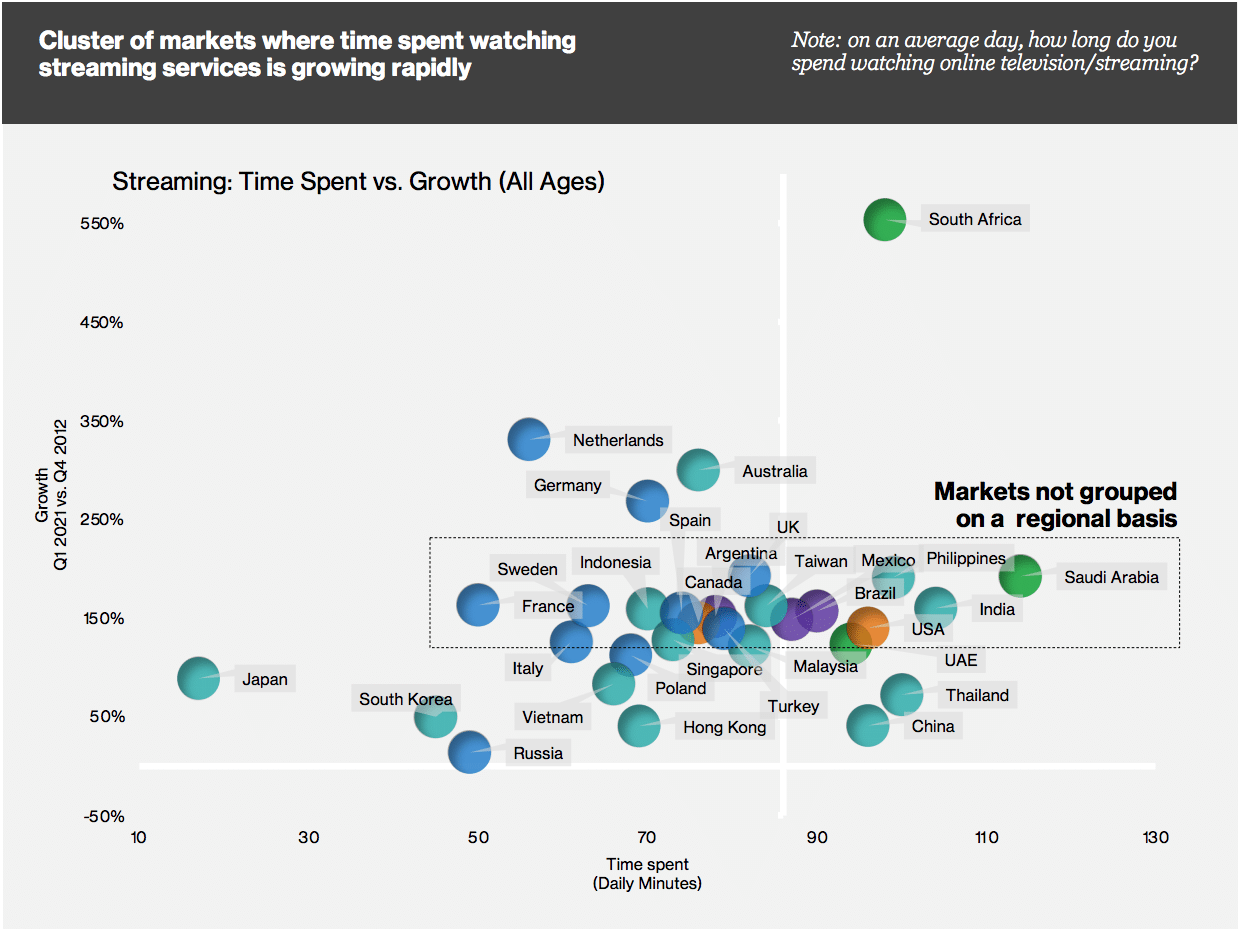

Provocation 03: Streaming is not a one-stop replacement for lost TV time

Of all the regions we’ve studied, APAC stands out for several reasons. One of the most interesting is the erratic growth of streaming as a replacement for TV. Some markets saw huge growth in streaming, especially during Covid (eg Australia). Others saw less dramatic growth but had high volumes already (eg Thailand). Others like South Korea saw only moderate growth from a moderate (by global standards) base. Throw in the complexity of non-commercial platforms like Netflix sucking up the minutes, and the question of streaming as a replacement for TV becomes a complex one.

What this means is that we can’t simply suggest ‘take x% of the TV budget and put it in broadcastervideo-on-demand (BVOD)’ as an answer to our problem. The lost minutes in linear TV are often not being replaced by commercially available streaming at a fast enough rate. Media planners will need to think more carefully about diversifying our screens mix. TV and video planning best practice now extends across Public (out-of-home and cinema), Private (desktop, mobile and tablet) and Shared (TV and connected TV) to take in the full gamut of different options to balance reach and effectiveness.

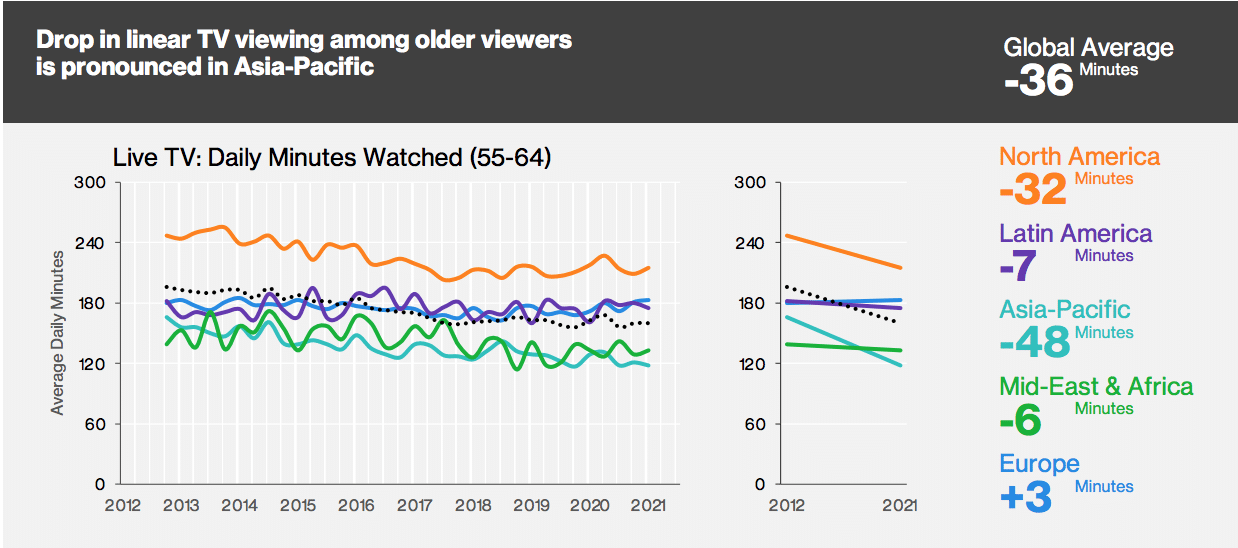

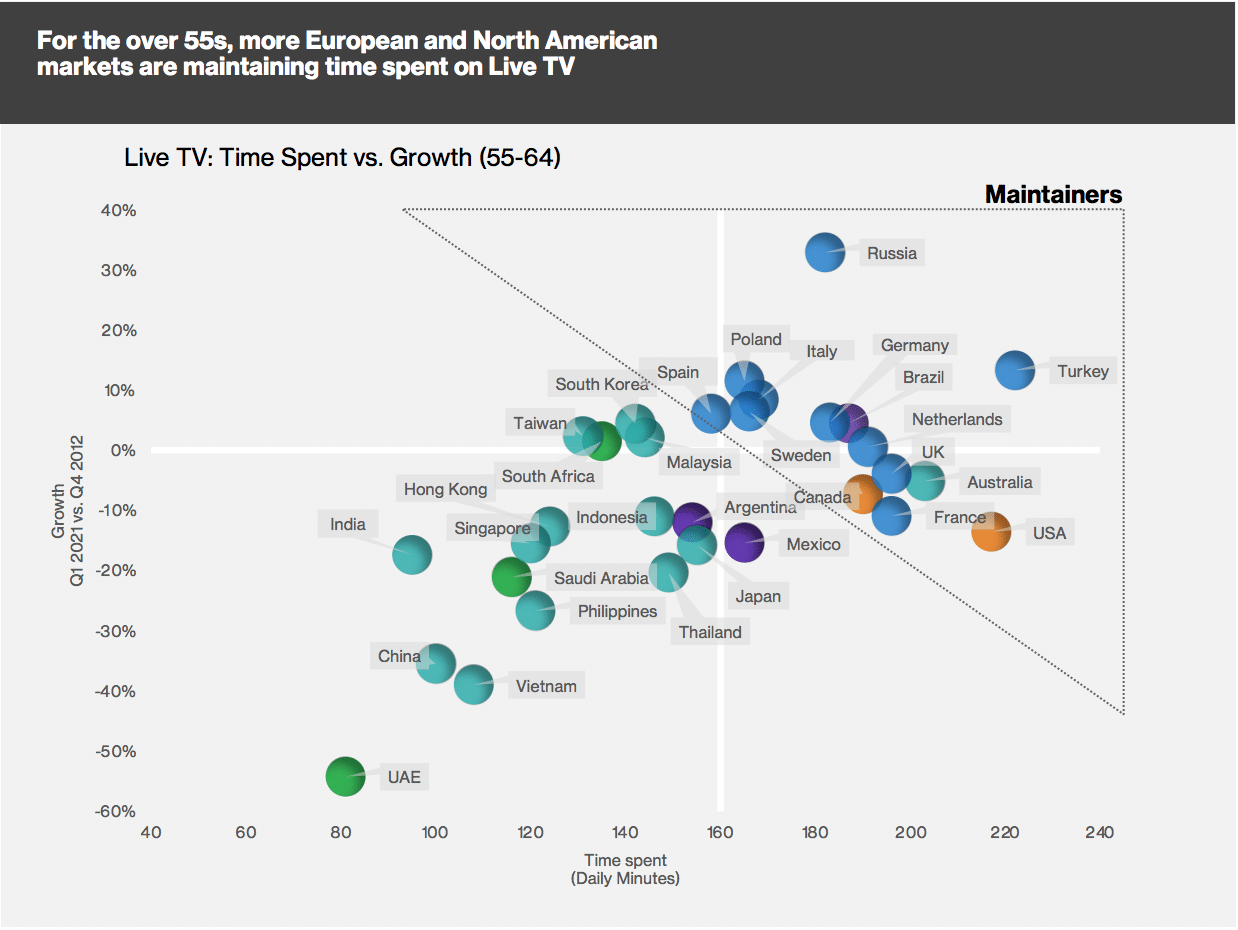

Provocation 04: Don’t take older viewers for granted – wherever you are

A further APAC trend that should be watched closely is what’s happening at the other end of the age spectrum. There’s a real risk that while all our attention is being captured by the hard-to-reach young, we miss what’s going on with older viewers.

As discussed, the prevailing global trend is TV’s struggle to hang on to young viewers who were previously there. But in APAC (outside AUNZ), it may be a case of young people never joining in the first place – then going straight for mobile, online video and streaming services. In which case, it is older audiences who we should be thinking about most.

There’s a way to look at these numbers and wonder if they presage the next 10 years in regions like EMEA for example. As generations of light linear TV viewers grow older and work their ways through the age brackets, the next wave of declines will inevitably be seen in the middle and then older age brackets.

So, what should planners do? Firstly, don’t panic! Second, start testing diversified mixes of channels among different audiences right now. We know from the latest IPA Touchpoints study that the media worlds of the young and old overlap now by a miniscule amount (as little as 8%). Planners need to use this to our advantage with different media mixes now deployed against different audience groups. Diversification isn’t just for the young – it’s time to get serious with the old too.

Provocation No5: Never let a TV crisis go to waste

It’s a cheery cliché, but the decline in classic TV viewing presents an opportunity as much as a threat. In losing the power of a single ‘catch all’ channel to do everything, we have the chance to look afresh at how media mixes are put together.

For example, if the role of linear TV is no longer to provide the baseline for your plan, then maybe it’s freed up to become ‘the special’. Rather than simply planning enough 30- or 15-second spots to reach 60% of an audience, once (a pretty standard buying benchmark), how about a Superbowl ad or the Champions League Final? How about sponsoring a key show in a different way? How can you use talent and integrated segments in the show as replacements for conventional ad breaks filled with 15-second spots?

Certain areas of the TV landscape will endure, and these hold huge potential for brands to connect with consumers. Nothing beats the collective power of the sofa during a big sports match or the iconic Friday family movie on a rainy day. It’s a special place where planners who are willing to sacrifice reach for emotion and attention can reap dividends.

In closing the doors on one era of TV, we might just be able to bust open the roof on a new one.

Martin Yuill, Joint Head of Data Insight, Worldwide

Elliott Millard, Head of Planning, UK

Catherine Wolkers, National Head of Research & Insight,Australia

James Boardman, National Strategy Partner, Australia